Cornerstones of Compression: “Making Cold”

March 31, 2025

This continues a series of Cornerstones of Compression corollary articles that provide an historical look at the industries that drove the invention and technological evolution of compressors and that supported the growth and development of the industries that depended on them. This issue introduces compressors developed for “making cold.”

In addition to the demands of air blowing for blast furnaces, ice making and refrigeration was one of the needs that drove the development of early compressors during the industrial revolution. Discovering how to make cold changed the way people ate and lived, almost as profoundly as discovering how to cook.

Mechanical Refrigeration and Ice Making

Various methods of cooling and refrigeration using natural ice and primitive methods of evaporative cooling date back to ancient Egyptian and Greek civilizations. As far back as 1607, various frigorific mixtures were used by scientists for ice making and refrigeration, the most common being salt and ice. This was employed by Fahrenheit in 1762, when he placed the freezing point of water at 32˚F (0˚C). As early as the middle of the eighteenth century, scientists were experimenting with vacuum to produce rapid evaporation and refrigeration. Dr. William Cullen first used this principle in 1755 to produce ice by purely mechanical means. He reduced the atmospheric pressure with an air pump, which increased the evaporation of water to produce intense refrigeration and ice.

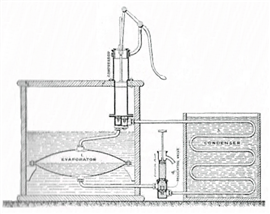

Perkins hand-operated piston type compressor, c.1834.

Perkins hand-operated piston type compressor, c.1834.

A few years after the invention of the vacuum ice machine, various chemical means were discovered. In the 1820s, Humphrey Davy and Michael Faraday further advanced mechanical refrigeration when they discovered that compressing and liquefying ammonia could chill air when the liquefied ammonia was allowed to evaporate. In 1824, English patents were obtained for refrigerating by the use of sulfuric acid. In 1834, Jacob Perkins is generally credited with inventing the first practical machine that was the forerunner of the modern compression apparatus. His machine, which employed a hand-operated piston type compressor as shown in Fig. 1, was substantially improved by 1856 and brought into practical use in the refrigeration of breweries and food products.

Process improvements and equipment continued a rapid evolution, and in 1850, Prof. A.C. Twinning of New Haven, Connecticut patented an apparatus that used a double acting 8.5 in. (216 mm) diameter by 16 in. (406 mm) stroke vacuum and compression pump. Also in 1850, Dr. John Gorrie of Apalachicola, Florida patented an ice making machine that, for the first time, used a rotating shaft with eccentrics and linkages to move compressor pistons inside vertically oriented cylinders for compression and vacuum generation.

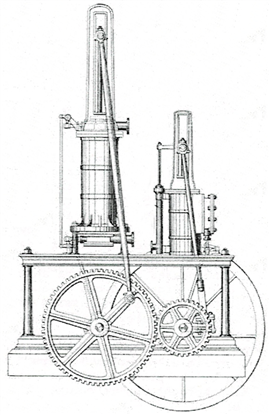

Harrison ice making machine geared directly to a steam engine frame, c.1859.

Harrison ice making machine geared directly to a steam engine frame, c.1859.

In 1859, Australian James Harrison introduced an ice making machine that was geared directly to a steam engine frame as shown in Fig. 2. Developments continued rapidly, with major advancement resulting from Prof. C.F.G. Linde’s introduction of the ammonia refrigeration machine in 1873-1875. Linde is considered the foremost exponent of the ammonia compression system of refrigeration. His machines were in operation in German breweries by 1876, and he obtained U.S. patents in 1880.

As mechanical refrigeration was produced by the compression and subsequent expansion of a gaseous fluid such as ammonia, sulfuric acid and air, more uses were being found than the inventors ever dreamed of. This led to a number of U.S. companies developing large refrigeration compressors in the decade from 1880 to 1890.

Charles J. Ball installed his first absorption ice making machine at Sherman, Texas in 1878. It was a modification of an earlier vacuum machine developed by Edmund Carre’. The ammonia pumps, water pumps, boiler feed pump, brine pump, etc. were driven by belts from shafting run by a slide valve steam engine. With an installed cost of $12,000, the machine made about five tons of ice daily with one ton of coal. Ball’s first compression machine of his own manufacture was erected at Dallas, Texas in 1887. The company, known as the Ice and Cold Machine Co., operated successfully in St. Louis, Missouri for many years.

The Emergence of Large Reciprocating Refrigeration Compressors

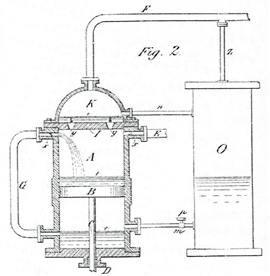

As shown in this patent drawing, De La Vergne used lubricating oil both ahead and behind the compressor piston to avoid superheating, 1876.

As shown in this patent drawing, De La Vergne used lubricating oil both ahead and behind the compressor piston to avoid superheating, 1876.

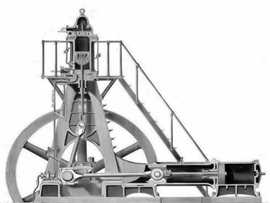

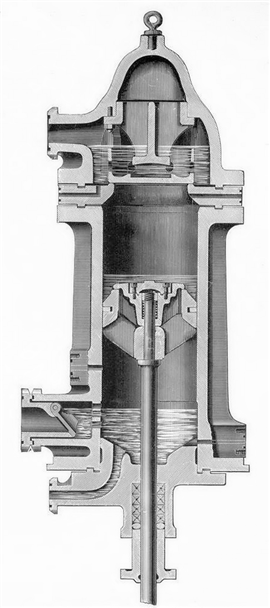

The first De La Vergne refrigeration machine, which became one of the most popular, was placed in the Hermann Brewery in New York City, New York in 1878. The inventor of the original apparatus, John C. De La Vergne, had long been engaged in the produce business in New York previous to becoming identified with the brewing industry in 1876. This turned his attention to artificial refrigeration, and in 1880 he formed the De La Vergne Refrigeration Machine Co., using patented technology for compression and expansion of ammonia with the use of lubricating oil both ahead and behind the compressor piston to avoid superheating, as shown in Fig. 3. By 1884, after further development, De La Vergne was manufacturing refrigeration machines for other breweries. The section view of an 1884 De La Vergne refrigerating compressor in Fig. 4 shows the horizontal steam cylinder and vertical single-acting compressor cylinder. The cylinder close-up in Fig. 5 shows the cooling and sealing liquid above and below the piston at the bottom of the cylinder. Vertical orientation of the cylinder was necessary to expel the liquid out of the cylinder effectively with each stroke. After overcoming fears of the effect of ammonia leaks on meat, the system found its way into meat packing plants as well. By 1890, De La Vergne was a huge firm, having manufactured almost 250 steam engine-driven ammonia compressors that provided refrigeration for most of America’s breweries as well as ice plants, cold storage facilities, and any other places throughout the world needing refrigeration.

De La Vergne refrigerating compressor, 1884.

De La Vergne refrigerating compressor, 1884.

Although De La Vergne and Ball were among the U.S. refrigeration compressor pioneers, companies such as Frick, Weiser & Vilter and York would soon dominate the rapidly developing industry.

De La Vergne compressor cylinder showing cooling and sealing liquid above and below the piston.

De La Vergne compressor cylinder showing cooling and sealing liquid above and below the piston.

MAGAZINE

NEWSLETTER

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM