Cornerstones: Fairbanks Morse 38A20 Dual Fuel Engine

April 30, 2024

The Cornerstones of Compression series has highlighted many significant products over more than 160 years of continuous progress. However, there were also some great engine and compressor ideas that were unsuccessful. This brief Cornerstones of Compression corollary series features several development failures. By Norm Shade

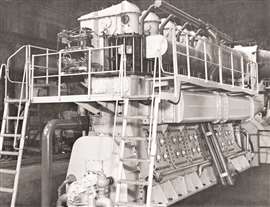

One of the first installed Fairbanks-Morse 38A20 engines, 1968.

One of the first installed Fairbanks-Morse 38A20 engines, 1968.

In the early 1960s, 140-year-old Fairbanks-Morse, which had never built an engine larger than 5400 hp (4027 kW), saw an opportunity in the European-dominated big-diesel market. Fairbanks’ planned to build a “medium-speed” engine that would be far lighter and more compact than any big diesel ever built. Its 38A20 engine was intended to push per cylinder ratings to an unprecedented 1000 hp (746 kW) and later to 1250 hp (932 kW).

The two-cycle 38A20 engines operated on the thoroughly proven opposed-piston principle developed by Fairbanks-Morse over 30 years earlier and used in over 7000 production engines. The uniflow 38A20s included six- and nine-cylinder inline and 12- and 18-cylinder vee models with per cylinder ratings of 1000 hp (746 kW) at 400 rpm and 1250 hp (932 kW) at 450 rpm.

Orders came quickly

On paper, the machines looked good, and the Beloit, Wisconsin company’s marketing was aggressive. In 1966, before any 38A20s had yet been built, Anaconda Company ordered eight 12,000 hp (8949 kW) models. Several utilities also ordered the big engines, and in 1967 Litton ordered 15,000 hp (11,186 kW) marine versions for four large tankers that were being built. Bahamas Electric Company (BEC), which was desperate for additional power generation, took delivery of two 6000 hp (4474 kW) six-cylinder engines in 1968. The first engine failed during tests in July; the second tore itself apart in August and was returned for overhaul. Although these events worried Fairbanks, BEC ordered two 12,000 hp (8949 kW) 38A20 engines. The “smaller” engines continued to have problems, the Bahamas were plagued by power cutbacks and failures, and the matter became an urgent political matter. When Fairbanks finally said that it would not be able to deliver the bigger diesels even by the end of 1969, BEC cancelled the contract and ordered European gas turbines.

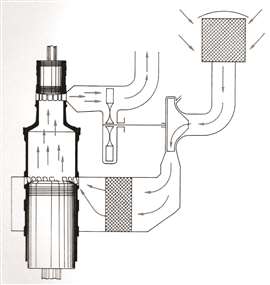

Cross-section of the 38A20 inline opposed-piston engine, which was built in six- and nine-cylinder configurations.

Cross-section of the 38A20 inline opposed-piston engine, which was built in six- and nine-cylinder configurations.

Anaconda also got its machines in 1968. They worked reasonably well on diesel fuel; however, they were to run most of the time on cheaper “dual fuel”, a mixture of natural gas and light oil. When the first machine was switched from diesel, it jammed, and Anaconda discovered that it had six troublesome monsters on its hands, plus two others that were planned for a Chilean mine. While a team of Fairbanks engineers struggled with one machine, the others continued running imperfectly on diesel. Anaconda suffered production losses, the diesels produced uneven power and belched black smoke, and it was difficult getting a million gallons of diesel fuel a month to the mine near Tucson, Arizona. In May 1970, Anaconda cancelled the contract and turned to commercial power.

Unfortunately, the 38A20 had many major shortcomings. It was not strong enough, it could not cool itself, and especially at the 3700 ft (1128 m) altitude of the Anaconda mines, it could not get enough air. Cylinder liners and rocker arms cracked. Pistons would stick, connecting rods would break and fly about, and gases would explode in the crankcase. Just about everything that could go wrong had gone wrong with the 38A20s. The chief designer left for early retirement. Management changes brought a new president, chief engineer and project head. Consultants shuttled back and forth from Europe. Problems continued as the company was being run by financial people who thought technical problems were trivial. Through it all, parent company Colt maintained an official optimism. Its 1968 annual report said simply that “the first models...are already in use by domestic utilities for stationary base load and standby power generation.” But by the end of 1968, Fairbanks had quit selling 38A20s.

Meanwhile, while it wrestled with the 1000 hp (746 kW) per cylinder machines in the field, Fairbanks was building four engines of 1250 hp (932kW) per cylinder for Litton and another for a U.S. Steel Corp. ore carrier. The Litton machines, due in late 1969, were behind schedule. Fairbanks said it could deliver in the summer of 1970, but that the engines would need another year of work before they could meet their power ratings. Faced with losses, Litton sued Colt to get back $3 million in progress payments, plus $25 million in damages.

Expensive lesson

Remarkably, Colt extracted itself from the lawsuit and held onto the business by furnishing two 7500 hp (5593 kW) Pielstick diesels for each ship. Pielstick engines

were very successful engines built under license. Colt bought six from European companies while Fairbanks geared up to manufacture Pielstick engines under license in Beloit, building two for the Litton order.

Although Colt took an $18 million write-off in 1970, it never admitted that the program was a failure. But it was clear that Fairbanks’ management did not fully appreciate the technical risks, selling the early machines before being fully developed and shipping them before being fully tested. The 38A20 might have appeared to be simply a scale-up of the two-cycle opposed-piston engine that the company had been making for over 30 years, but there were significant differences. Most notable was that the upper and lower pistons were different sizes. The fuel is ignited as the pistons converge, and combustion forces them apart. In the 38A20, the upper crankshaft is on one side and driven by rocker arms connected to the upper pistons. To reduce the load on this linkage, the upper piston was only half the diameter of the lower piston. This led to high stresses in the cylinders at the diameter change, which were exacerbated by high combustion temperatures. In a two-cycle engine, the pistons work on every revolution of the crankshaft, and cooling of the cylinders becomes difficult as power levels increase.

Fairbanks Morse claimed that its two-cycle 38A20 Uniflow concept optimized scavenging.

Fairbanks Morse claimed that its two-cycle 38A20 Uniflow concept optimized scavenging.

Without expensive hand-fitting, the manufacturing standards that had been acceptable for lower-power engines were inadequate for the higher-power 38A20. In the end, Fairbanks and Colt took extraordinary steps to reduce the impact of the 38A20 fiasco on future business. It was speculated that the 38A20 engine program cost Colt/Fairbanks more than $100 million. Ultimately, Fairbanks-Morse survived to remain a prominent manufacturer of large engines, but no more 38A20 engines were sold. The company recovered and thrived by continuing to build traditional lower-rated opposed-piston models and growing its large medium-speed engine presence with the Pielstick design. CT2

MAGAZINE

NEWSLETTER

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM