Cornerstones of Compression: Evolution of iron & steel compressors

August 16, 2024

This story continues a series of Cornerstones of Compression corollary articles that provide a look back at the industries that drove the invention and technological evolution of compressors that supported their growth and development. This issue completes the evolution of compressors used for making iron and steel.

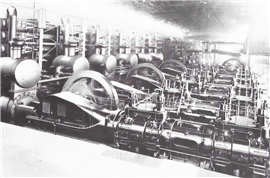

A vertical steam powered machine with 96 in. (2438 mm) diameter air cylinders shown in the Cooper plant in 1907.

A vertical steam powered machine with 96 in. (2438 mm) diameter air cylinders shown in the Cooper plant in 1907.

As industrialization swept the U.S. in the 1800s, blast furnaces became increasingly common, growing in number and size. Several companies began producing air blowing engine-compressors. One of the first was the C. & J. Cooper Company of Mount Vernon, Ohio. Its first blowing engine-compressor in 1852 had one 18 in. (457 mm) steam cylinder and two 48 in. (1219 mm) diameter air cylinders that delivered air at 3 psig (0.2 bar).

Another early manufacturer of air blowing reciprocating engine-compressors was the Edward P. Allis & Company, later Allis-Chalmers, of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Allis began producing steam engines in 1869, some of which were used for air blowing compressors.

Between 1872 and 1913, major developments in air blowing engine-compressors occurred. Ever larger units were developed that could produce very large volumes of blast pressure at 9 psig (0.62 bar). For example, in the 1890s, Allis was building vertical 60 in. (1524 mm) stroke machines with 42 in. (1067 mm) diameter steam cylinders and 84 in. (2134 mm) diameter air cylinders, as shown in last month’s issue.

In 1903, Cooper built the largest horizontal Corliss compound steam engine-compressor ever built for air blowing. In 1907, the company was building vertical steam powered machines with 96 in. (2438 mm) diameter air cylinders as shown in Fig. 1. Cooper produced an estimated 360 blowing engine-compressors averaging 500 hp (373 kW) per unit over a 60-year span, transitioning from horizontal designs to vertical compound engines in the later years.

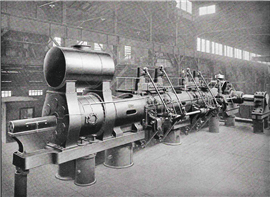

Other companies that were notable for producing large reciprocating engine-compressors for air blowing were Milwaukee-based, Nordberg Manufacturing Company, the Buffalo, New York-based Snow Steam Pump Works, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based companies, Mesta Machine and Westinghouse. A large 60 in. (1524 mm) stroke Mesta horizontal gas engine air blowing compressor with a 96 in. (2438 mm) diameter air cylinder is shown in Fig. 2.

A huge Mesta Machine horizontal gas engine air blowing compressor, 1914.

A huge Mesta Machine horizontal gas engine air blowing compressor, 1914.

20th century blast furnaces required a tremendous amount of air - about two tons for every ton of iron produced. Although built in the early 20th century, the huge air blowing engines represented the pinnacle of 19th century technology. Reciprocating steam engines powered the industrial revolution, and gas engines that followed were the next logical evolutionary step.

Waste Gas Engine Powered Air Blowing Compressors

Around the turn of the century, several manufacturers developed gas engines that used the “waste” gas produced from blast furnaces as fuel. This eliminated the need for steam boiler fuel and increased the plant efficiency. The gas engines were used for air blowing and also to drive electric generators. In 1914, Mesta built large 60 in. (1524 mm) stroke horizontal single tandem gas engines with an 84 in. (2134 mm) diameter double-acting blast air blowing cylinder. Each air cylinder had 22 valves.

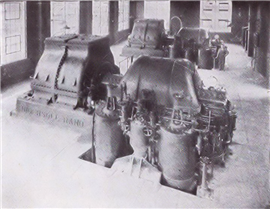

Fig. 3 shows three Allis-Chalmers twin-tandem gas engine compressors that supplied air to the blast furnaces at the Illinois Steel Co. These gas engines were fueled by waste gas produced by the furnaces.

Three Allis-Chalmers twin-tandem gas engine air blowing compressors at the Illinois Steel Co.

Three Allis-Chalmers twin-tandem gas engine air blowing compressors at the Illinois Steel Co.

Turbo-Blowers

Most blowing engines operated at 32 to 35 rpm and produced an average air pressure of 20 psig (1.4 bar). In operation they were magnificent to behold. The 20 ft. (6.1 m) diameter flywheels and the movement of the gears, crankshafts, and levers made the machines look almost alive. But all those moving parts required constant attention, adjustment, and lubrication. The sheer size and complexity of this huge reciprocating machinery led to an opportunity for centrifugal air blowers and compressors.

The first use of rotary blowers for iron or steel melting occurred in 1860 when Francis M. and Philander H. Roots patented a lobed blower that was used to provide air for melting iron in foundries, and they found wide use in small operations. With the first practical centrifugal compressor appearing in France in 1899, Ingersoll-Rand saw an opportunity for centrifugal technology in high flow, low pressure air compression applications. By 1912, Ingersoll-Rand introduced the first U.S.-built centrifugal air compressor, a tandem, steam turbine-drive unit that produced air at 90 psig (6.2 bar). A 1916 advertisement offered turbo blowers and compressors for all industrial purposes.

The first turbo-blower, installed in 1910 for a blast furnace in the Empire Steel Co. in New Jersey, was the direct ancestor of the modern centrifugal turbocompressor blower. Ingersoll-Rand was the dominant manufacturer of large centrifugal turbo-blowers for blast furnaces, an example of which is shown in Fig. 4.

Two Ingersoll-Rand 100,000 cfm (2832 m3/min) turbo-air blast furnace air blowers driven by steam turbines, c.1950.

Two Ingersoll-Rand 100,000 cfm (2832 m3/min) turbo-air blast furnace air blowers driven by steam turbines, c.1950.

Typical turbo-blowers could produce an average of 43,000 cfm (1218 m3/min) of air at 20 psig (1.4 bar), replacing four or more huge reciprocating engine-compressors. Larger machines evolved to produce air flows two to three times larger. In operation, the turbo-blowers were in many ways the opposite of the reciprocating engine air blowing compressors. There was little to see, because the moving parts were under cover, and while great care was needed to install and repair them, they required maintenance only at infrequent intervals. Large axial blast air blowers, such as shown in Fig. 5, provided even larger flows. These were the final major step in more than 1200 years of blast air blowing improvement.

Dinosaurs Expire With Declining U.S. Steel Industry

In the late 1920s and through the Great Depression, reciprocating steam and gas engine blowing compressors continued running where already installed, but most new blast furnaces incorporated electric motor, steam turbine or diesel engine powered turbo-compressors (axial and centrifugal types) that could deliver large volumes of air at pressures of 57 psig (3.9 bar) or more. The majority of these in the U.S. were produced by Ingersoll-Rand. Older steel plants began to close in the 1950s, and by the late 1970s, essentially all of the huge reciprocating units had been retired.

Large axial blowers were the final step in more than 1200 years of blast air blowing improvement.

Large axial blowers were the final step in more than 1200 years of blast air blowing improvement.

MAGAZINE

NEWSLETTER

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM